Video Link: https://vimeo.com/291342022

Video Download: Click Here To Download Video

Video Stream: Click Here To Stream Video

Video Link: https://vimeo.com/291342104

Video Download: Click Here To Download Video

Video Stream: Click Here To Stream Video

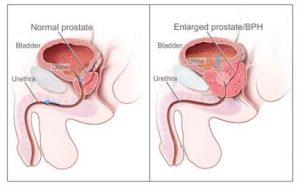

Prostate cancer is the most common tumor in men. The American Cancer Society estimates that 220,800 men will be diagnosed with the disease in 2015.

According to standard medical theory, prostate cancer typically turns deadly after tumors stop responding to drugs that block the production of testosterone and its receptors.

According to standard medical theory, prostate cancer typically turns deadly after tumors stop responding to drugs that block the production of testosterone and its receptors.

Therefore, for years, urologists have treated prostate cancer by decimating a man's testosterone levels, a treatment that is formally known as androgen deprivation therapy.

Medical school taught that this was “The Holy Grail” of stopping prostate cancer dead in its tracks.

Standard treatment for prostate cancer is chemical castration, drugs that cut the body’s production of testosterone and related hormones.

The fact that this treatment often resulted in hellish side effects was either ignored or rationalized by the depressing mantra of “at least he's still alive.”

So on and on it went.

Men were forced to choose between death by the spread of cancer or losing their manhood and all of the horrifying consequences that went with that loss: sexual dysfunction/impotence, hot flashes, joint pain, loss of muscle tone and strength, increased fatigue, and a sense of hopeless depression.

However, the Times are Changing

A new study shows that the exact opposite of the standard treatment may be far more efficient in combating prostate cancer.

In this study, testosterone replacement therapy (TRT), which increases a man's testosterone levels, was shown to slow the progression of untreatable prostate tumors in some patients.

The hormone testosterone, which supposedly fuels prostate cancer growth, unexpectedly blocked the disease in some instances, according to researchers who found it made tumors more vulnerable to treatment in some patients.

The hormone testosterone, which supposedly fuels prostate cancer growth, unexpectedly blocked the disease in some instances, according to researchers who found it made tumors more vulnerable to treatment in some patients.

This finding came as a shock to many, and the race was on to discover how and why this unexpected result was happening.

The Problem with Traditional Treatment

To some, the traditional approach of lowering testosterone levels to stop prostate cancer defied common sense.

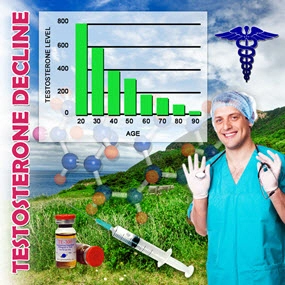

It is a known fact that young men are flooded with testosterone. But young men are very seldom diagnosed with prostate cancer.

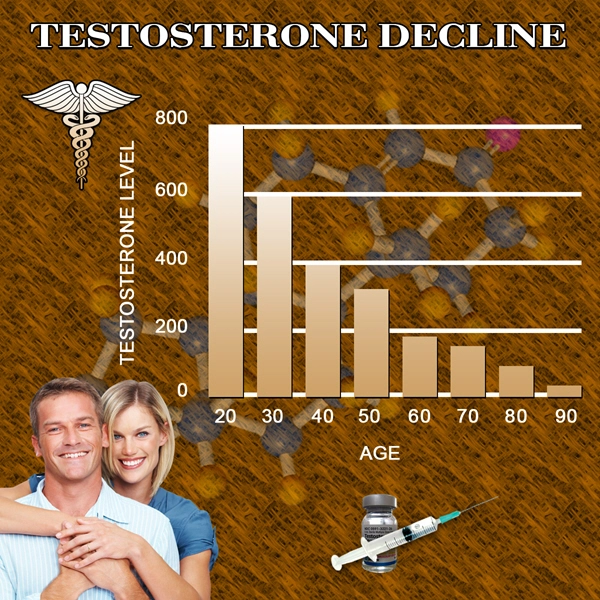

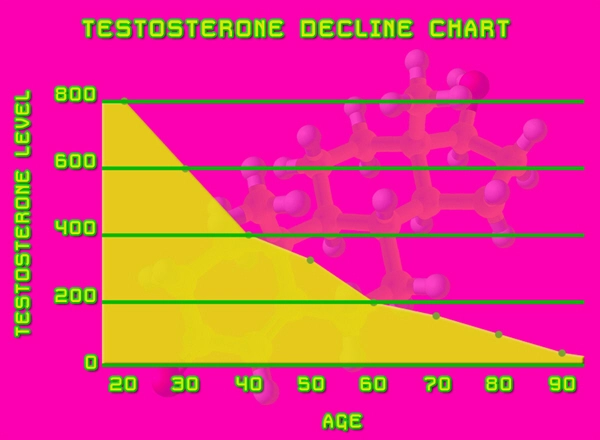

As men age, beginning around 30, testosterone production begins to decline at a rate of approximately 10% per decade.

Do the math.

This means that an 80-year-old man has around 50% of the testosterone that he had at age 30.

But which age group is being diagnosed with prostate cancer?

The 80-year-old men!

This begs the question: Where in the world did the idea that annihilating a man's testosterone levels would prevent prostate cancer from spreading?

The connection between average to high levels of testosterone and prostate cancer was first promoted in the early 1940s by Dr. Charles B. Huggins, a Chicago  urologist.

urologist.

In researching benign enlargement of the prostate, Huggins experimented with castration of dogs (the only other species besides man that suffers from prostate problems).

Huggins noticed that after castration, the dogs experienced shrinkage of the prostate.

And when their prostates were removed...no more cancer.

This removal led to Huggins trying the same thing on humans. It was known that castration reduced testosterone levels in the bloodstream.

He then took a group of men whose prostate cancer had spread to their bones and lowered their testosterone levels, either by administering estrogen, or castration.

Also, a blood test called acid phosphatase was elevated in men with metastatic cancer (cancer that spreads outside the prostate gland to the lymph nodes, bones, or other areas).

If the testosterone levels of the men were lowered, acid phosphatase dropped considerably, usually within days.

Taking it one step further, Huggins made the shocking discovery that raising testosterone levels caused acid phosphatase to rise, and also resulted in “enhanced growth” of prostate cancer.

As a result of his work, Higgins was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1966, for determining that prostate cancer grew or shrank depending on testosterone levels.

More important, this became the only officially approved method of treatment for prostate cancer and has been mostly unquestioned until recently.

These accolades were bestowed upon the good doctor in spite of the fact that in his study, only three men had received testosterone injections.

But the results were only given for two of them, and one of them had already been castrated! Therefore, the results were just for a single man who had received testosterone injections with any prior hormonal manipulation.

Most studies are ignored unless they have several thousand participants...but not this one.

No one checked the numbers.

Believe it or not, this was the study that somehow became unassailable dogma to generations of urologists, and condemned countless victims to a lifetime of needless suffering and misery.

The Theory Begins to Crack

It was noted that after androgen deprivation therapy, cancer cells usually adapt to the low hormone levels and resume growing.

For example, they sometimes crank out more of the receptor molecules stimulated by testosterone or switch to a version of the receptor that doesn’t need testosterone to prompt growth.

Although researchers have devised new treatments to counteract this resistance, such as drugs that block the testosterone receptor, tumors often quickly develop resistance to them as well.

Studies of cancer cells in a dish and tumors in animals have discovered a paradox about so-called castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Cancer cells that expand when testosterone is scarce often die when exposed to high levels of the hormone.

Experiments suggest that the extra hormone interrupts DNA duplication and leads to DNA fractures, which can kill a cell.

This paradoxical relationship means that testosterone doses could be beneficial against resistant tumors.

Medical oncologist Michael Schweizer, from the University of Washington, Seattle, and colleagues from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, put this idea to the test.

In a trial of 16 patients, investigators used a new method, dubbed “bipolar androgen therapy,” to attack tumors that had built resistance.

Patients were given monthly testosterone shots while simultaneously receiving drugs to block their natural production, creating huge swings in levels of the hormone.

Most of their tumors had spread, or metastasized.

In the study, the men continued to receive chemical castration therapy, but every 28 days the researchers also injected them with testosterone and two weeks of a chemotherapy drug called etoposide.

Men who showed decreases in PSA levels after three cycles were continued on testosterone injections alone.

Each shot spiked blood testosterone levels well above average, but they gradually declined until they were close to the level produced by chemical castration.

The rationale for these oscillations, Schweizer says, is that “you don’t allow prostate cancer cells to get accustomed to one testosterone environment.”

The hormone peaks will kill cancer cells that have adapted to low testosterone, whereas the valleys will smother cells that require testosterone to grow.

Of the 16, two did not complete the study: One died of pneumonia and sepsis due to the etoposide, and the other experienced prolonged erection, a side effect of the testosterone.

Of the 14 remaining in the trial, seven experienced a dip in their PSA levels of between 30 and 99 percent, an indication their cancers were stable or lessening in severity. Seven of the men showed no decrease in PSA.

Besides, four of the seven men stayed on testosterone therapy for 12 to 24 months with continued low PSA levels.

Of 10 men whose metastatic cancers could be measured with imaging scans, five experienced tumor shrinkage by more than half, including one man whose cancer completely disappeared.

“The fact that half of the guys who got through three cycles [of treatment] showed a response is encouraging,” Schweizer says.

"Surprisingly, we saw PSA reductions in all of 10 men, including four whose PSA didn't change during the trial, who were given testosterone-blocking drugs after the testosterone treatment," says Dr. Samuel Denmeade, the senior author of the paper and an oncologist at Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center in Baltimore.

"Surprisingly, we saw PSA reductions in all of 10 men, including four whose PSA didn't change during the trial, who were given testosterone-blocking drugs after the testosterone treatment," says Dr. Samuel Denmeade, the senior author of the paper and an oncologist at Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center in Baltimore.

The scientists say these results suggest that testosterone therapy has the potential to reverse the resistance that eventually develops to testosterone-blocking drugs like enzalutamide.

Three of the study participants have died since the survey began in 2010; the rest are still alive.

During the cycles of etoposide, many of the men experienced the usual side effects of chemotherapy, including nausea, fatigue, hair loss, swelling, and low blood counts.

In men receiving only the testosterone injection, however, side effects were rare among the men and usually low grade.

Over time, however, the advantages of testosterone injections decreased.

PSA levels began to rise after about seven months, suggesting renewed growth by the tumors.

But even a short-term response could extend the lives of patients because prostate cancer that is resistant to chemical castration is usually incurable, Schweizer notes.

Although a few previous studies attempted to measure the effects on prostate cancer of boosting testosterone levels, they didn’t provide the massive doses of the hormone necessary to kill resistant cancer cells, he says.

So the new work “is a first step toward finding out who will benefit from this treatment.”

“This is the most lethal form of prostate cancer,” said Dr. Schweizer. “It's the one that's the most resistant, and once people progress to this stage, it’s when we start to worry that they’re at a much higher risk of dying from prostate cancer.”

Some researchers and doctors were concerned that testosterone treatment might accelerate tumor growth, notes Charles Ryan, a cancer endocrinology researcher, and physician at the University of California, San Francisco, who wasn’t involved in the work.

But the study shows that “there’s potentially a substantial number of patients for whom this treatment is not harmful but is possibly beneficial.”

However, he’s not going to change how he treats prostate cancer patients until researchers perform further studies that confirm the effects of testosterone and clarify the treatment’s risks.

“They have intriguing clinical data,” says medical oncologist and prostate cancer researcher Christopher Logothetis of the University of Texas Cancer CentMD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, who also wasn’t connected to the study.

But he was disappointed that the team didn’t test biopsy samples from the subjects to determine how testosterone was affecting the tumors.

That analysis is essential so that researchers can figure out how to predict which patients will benefit from the treatment and which might be harmed, he says.

‘Unexpectedly Promising’

“This was a small study, and it was a weird idea to give men with prostate cancer testosterone,” said Dr. Denmeade. “The results were unexpectedly promising, and we’ll need a lot more study. But this cycling on and off of testosterone could become a part of the treatment.”

This research is a deadly severe study, and it can have grave consequences.

One patient died during the trial from pneumonia linked to the chemotherapy that was part of the treatment approach.

of the treatment approach.

A prolonged erection, a possible side effect of testosterone therapy, led another patient to drop out of the trial.

Denmeade warns that the timing of testosterone treatment used in his research is critical and challenging to determine, and says men should not try to self-medicate their cancers with testosterone supplements available over the counter.

Previous studies, he adds, have shown that taking testosterone at the wrong time — mainly by men with symptoms of active cancer progression who have not yet received testosterone-blocking therapy — can make the disease worse.

The researchers exploited a vulnerability created as cancer cells adjust and become exquisitely sensitive in a low testosterone environment.

Previous lab work showed high testosterone could kill prostate cancer cells, though there wasn’t a compelling explanation for how the process worked, Schweizer said.

It may be that cancer cells that have adapted to the low-hormone environment can’t tolerate high levels of testosterone, according to an editorial summary that accompanied the paper.

In men whose prostate cancer spreads, doctors typically prescribe drugs that block testosterone production, but cancer cells eventually become resistant to this means of reducing the hormone, says Denmeade.

At that point, physicians switch to other drugs, such as enzalutamide, which block testosterone's ability to bind to receptors on prostate cancer cells.

Denmeade says the combination of medicines that block testosterone production and receptors, called androgen deprivation therapy, may make prostate cancer more aggressive over time by enabling prostate cancer cells to subvert attempts to block testosterone receptors.

And, as mentioned earlier, many men on these drugs experience horrible side effects.

With this context, the new study tested an approach based on the idea that if prostate cancer cells were flooded with testosterone, the cells might be killed by the hormone shock.

The cells also might react by making fewer receptors, which may make the prostate tumor cells vulnerable once more to androgen deprivation therapy.

The Exciting Good News

Denmeade says that more studies are being planned at Johns Hopkins and other hospitals.

Denmeade says that more studies are being planned at Johns Hopkins and other hospitals.

The Johns Hopkins researchers have another study underway that will involve 60 patients, and a larger, nationwide study is slated to begin this spring, Denmeade said.

"There has been a groundswell of interest in the idea of reversing resistance to androgen deprivation therapy. We have plenty of anecdotes and some evidence in this small study, but it's important to test it in larger groups of patients," he adds.

Two other studies of testosterone therapy in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer have begun, Schweizer notes, so researchers may soon have a better idea of whether the treatment is superior to current approaches.

Thus, the research continues and offers hope for the millions of men that are currently suffering from this deadly affliction, and the countless numbers of men who will develop the disease in the future.

Reference

Destroying the myth about testosterone replacement and prostate cancer

Contact Us Today For A Free Consultation

- Adverse Effects of Testosterone Therapy in Adult Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis [Last Updated On: July 2nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 4th, 2010]

- Low Testosterone Levels, Foods That Increase Testosterone Levels wwwSelf-Improvement-Bible.com [Last Updated On: November 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 30th, 2011]

- Low Testosterone in Men: The Next Big Thing in Medicine! - Abraham Morgentaler, MD [Last Updated On: May 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 3rd, 2011]

- How To Determine Testosterone Levels By Looking At Your Ring Finger [Last Updated On: December 7th, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 30th, 2011]

- Prolab Horny Goat Weed Testosterone Booster Supplement Review [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 19th, 2011]

- The Healthy Skeptic: Products make testosterone claims [Last Updated On: August 13th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 11th, 2011]

- How To Naturally Increase Testosterone [Last Updated On: November 21st, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 28th, 2011]

- Testosterone Production - Video [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 20th, 2011]

- Testosterone makes us less cooperative and more egocentric, study finds [Last Updated On: January 23rd, 2018] [Originally Added On: February 1st, 2012]

- Testosterone makes us less cooperative and more egocentric [Last Updated On: January 24th, 2018] [Originally Added On: February 1st, 2012]

- Too much testosterone makes for bad decisions, tests show [Last Updated On: April 30th, 2025] [Originally Added On: February 1st, 2012]

- Today in Research: Testosterone's Negative Effects; Diet Soda Death [Last Updated On: January 2nd, 2018] [Originally Added On: February 2nd, 2012]

- Testosterone drives ego, trips cooperation [Last Updated On: December 2nd, 2017] [Originally Added On: February 4th, 2012]

- FDA approves BioSante/Teva's testosterone gel [Last Updated On: April 28th, 2025] [Originally Added On: February 15th, 2012]

- 'Manly' Fingers Make For Strong Jawline in Young Boys [Last Updated On: December 1st, 2017] [Originally Added On: February 15th, 2012]

- Teva, BioSante Win U.S. Approval for Testosterone Therapy [Last Updated On: December 10th, 2017] [Originally Added On: February 15th, 2012]

- BioSante Gains on Approval of Testosterone Gel: Chicago Mover [Last Updated On: January 8th, 2018] [Originally Added On: February 16th, 2012]

- BioSante soars following drug approval from FDA [Last Updated On: December 26th, 2017] [Originally Added On: February 16th, 2012]

- Antibodies, Not Hard Bodies: The Real Reason Women Drool Over Brad Pitt [Last Updated On: December 24th, 2017] [Originally Added On: February 21st, 2012]

- Almark Publishing Releases Book From Mark Rosenberg, M.D. Revealing Natural Discoveries Associated With Low ... [Last Updated On: May 3rd, 2025] [Originally Added On: February 28th, 2012]

- Testosterone Replacement Clinic Comes to Kansas City with Potential to Help Thousands of Men [Last Updated On: May 2nd, 2025] [Originally Added On: March 1st, 2012]

- Study examines the relative roles of testosterone and its metabolite, dihydrotestosterone in men [Last Updated On: December 2nd, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 7th, 2012]

- The Role of 5{alpha}-Reductase Inhibition in Men Receiving Testosterone Replacement Therapy [Editorial] [Last Updated On: December 21st, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 7th, 2012]

- Effect of Testosterone Supplementation With and Without a Dual 5{alpha}-Reductase Inhibitor on Fat-Free Mass in Men ... [Last Updated On: January 3rd, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 7th, 2012]

- Why We Like Men Who Can Keep Their Cool [Last Updated On: December 30th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 7th, 2012]

- Testosterone And Heart Health [Last Updated On: May 1st, 2025] [Originally Added On: March 10th, 2012]

- Your Life on Testosterone: Overly Sure of Yourself, Unwilling to Listen [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 15th, 2012]

- Mayo Clinic-TGen study role testosterone may play in triple negative breast cancer [Last Updated On: December 8th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 23rd, 2012]

- A dose of testosterone might not cure what ails you [Last Updated On: January 23rd, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 25th, 2012]

- Green tea could aid athletes hide testosterone doping [Last Updated On: December 16th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 25th, 2012]

- TGen Study Role Testosterone May Play in Triple Negative Breast Cancer [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 26th, 2012]

- Testosterone low, but responsive to competition, in Amazonian tribe [Last Updated On: January 23rd, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 28th, 2012]

- Competition-linked bursts of testosterone are fundamental aspect of human biology, study of Amazonian tribe suggests [Last Updated On: December 25th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 28th, 2012]

- Playing football boosts testosterone levels by 30 percent! [Last Updated On: February 4th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 28th, 2012]

- Testosterone low, but responsive to competition, in Amazonian tribe -- with slideshow [Last Updated On: December 9th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 28th, 2012]

- The benefits of testosterone pellet therapy [Last Updated On: January 24th, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 29th, 2012]

- Low testosterone levels cause health woes [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 30th, 2012]

- Heart Failure Patients Getting Relief from Testosterone Supplements [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2025] [Originally Added On: April 21st, 2012]

- Study Finds Fatherhood Suppresses Testosterone [Last Updated On: May 4th, 2025] [Originally Added On: May 3rd, 2012]

- Low testosterone levels could raise diabetes risk for men [Last Updated On: January 26th, 2018] [Originally Added On: May 5th, 2012]

- Why low testosterone may increase your risk of diabetes [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 5th, 2012]

- Diabetes link to low testosterone [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 5th, 2012]

- Testosterone Linked to Weight Loss in Obese Men [Last Updated On: January 2nd, 2018] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2012]

- Testosterone may help weight loss [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2012]

- Testosterone-fuelled infantile males might be a product of Mom's behaviour [Last Updated On: December 25th, 2017] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2012]

- Testosterone-fueled infantile males might be a product of Mom's behavior [Last Updated On: January 6th, 2018] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2012]

- Testosterone supplements may help obese men lose weight [Last Updated On: January 5th, 2018] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2012]

- Testosterone supplements 'can help men lose their middle-aged spread' [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 12th, 2012]

- Some doctors question safety of testosterone replacement therapy [Last Updated On: January 20th, 2018] [Originally Added On: May 15th, 2012]

- Health Canada Approves New Testosterone Topical Solution for Men [Last Updated On: May 15th, 2025] [Originally Added On: May 15th, 2012]

- Environment trumps genes in testosterone levels, study finds [Last Updated On: May 8th, 2025] [Originally Added On: May 15th, 2012]

- Global Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) Industry [Last Updated On: May 7th, 2025] [Originally Added On: May 21st, 2012]

- Testosterone Fuels Boom, Swindler Sows Panic: Top Business Books [Last Updated On: January 13th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 2nd, 2012]

- Increase in testosterone drug use [Last Updated On: April 12th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 4th, 2012]

- Testosterone Promotes Agression Automatically [Last Updated On: January 29th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 9th, 2012]

- Testosterone shown to help sexually frustrated women [Last Updated On: January 27th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 9th, 2012]

- Research and Markets: Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) - Global Strategic Business Report [Last Updated On: December 23rd, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 12th, 2012]

- Proposed testosterone testing of some female olympians challenged by Stanford scientists [Last Updated On: January 30th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 14th, 2012]

- Testosterone Makes Bosses Into Jerks, Says Paul Zak [Last Updated On: January 8th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 14th, 2012]

- Testosterone Therapy: A Misguided Approach to Erectile Dysfunction (ED) [Last Updated On: May 10th, 2025] [Originally Added On: June 20th, 2012]

- New drugs, new ways to target androgens in prostate cancer therapy [Last Updated On: January 8th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 20th, 2012]

- Long-term testosterone treatment for men results in reduced weight and waist size [Last Updated On: January 19th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 23rd, 2012]

- Declining testosterone levels in men not part of normal aging, study finds [Last Updated On: December 27th, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 23rd, 2012]

- Low testosterone not normal part of aging [Last Updated On: December 22nd, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 25th, 2012]

- Testosterone Does Not Necessarily Wane With Age [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 25th, 2012]

- Overweight men can boost low testosterone levels by losing weight [Last Updated On: December 10th, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 25th, 2012]

- Testosterone-replacement therapy improves symptoms of metabolic syndrome [Last Updated On: January 14th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 26th, 2012]

- Testosterone therapy takes off pounds [Last Updated On: December 11th, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 26th, 2012]

- Weight loss may boost men's testosterone [Last Updated On: May 9th, 2025] [Originally Added On: June 27th, 2012]

- Low Testosterone? Study finds age may not be to blame [Last Updated On: May 12th, 2025] [Originally Added On: July 1st, 2012]

- Do you have low testosterone? [Last Updated On: December 15th, 2017] [Originally Added On: July 8th, 2012]

- Wall Streeters Buying Testosterone for an Edge [Last Updated On: May 11th, 2025] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2012]

- Beefy Wall Street Traders rub on testosterone [Last Updated On: February 20th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2012]

- Tale of two runners exposes flawed Olympic thinking [Last Updated On: December 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 19th, 2012]

- Genetic markers for testosterone and estrogen level regulation identified [Last Updated On: January 6th, 2018] [Originally Added On: July 20th, 2012]

- BUSM researchers identify genetic markers for testosterone, estrogen level regulation [Last Updated On: December 18th, 2017] [Originally Added On: July 20th, 2012]

- DRS. OZ AND ROIZEN: How to reap the benefits of normal testosterone levels [Last Updated On: December 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 21st, 2012]

- How Testosterone Drives History [Last Updated On: December 24th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 22nd, 2012]

- Testosterone replacement is "fountain of youth" for men [Last Updated On: January 3rd, 2018] [Originally Added On: July 27th, 2012]

- Pill for low testosterone in men heads for phase II clinical trials [Last Updated On: December 31st, 2017] [Originally Added On: August 2nd, 2012]

Word Count: 2270